Any man-made object or material that winds up abandoned on beaches is an indication of recklessness, thoughtlessness, or catastrophe. Former economic policies regarding garbage disposal will continue to haunt inhabitants of the region indefinitely.

Past ocean dumping and ocean-side landfill development practices are contributing to the on-going accumulation of anthropogenic debris offshore and on area beaches. In certain places (particularly around Raritan Bay and portions of New York Harbor) discarded building material, household/industrial garbage, and other waste materials have become a major constituent of shore deposits. Along ocean-front beaches the grinding action of waves is helping to break down these materials. However, the same wave energy, along with tidal and storm currents, are working to redistribute these materials throughout the marine and coastal environments.

The Fresh Kills Landfill is ranked as one of the largest landfills on Earth, yet it is only one of many landfills situated in the low coastal zone in the New York Bight. These great piles of rubbish are the lasting legacy of our times. If sea level were to rise as little as two meters tidal and storm currents would begin to rework and redistribute materials in most area landfills throughout the coastal region. Marine flooding would contribute to slumping of the landfills. Exposed debris would then be vulnerable to combustion.

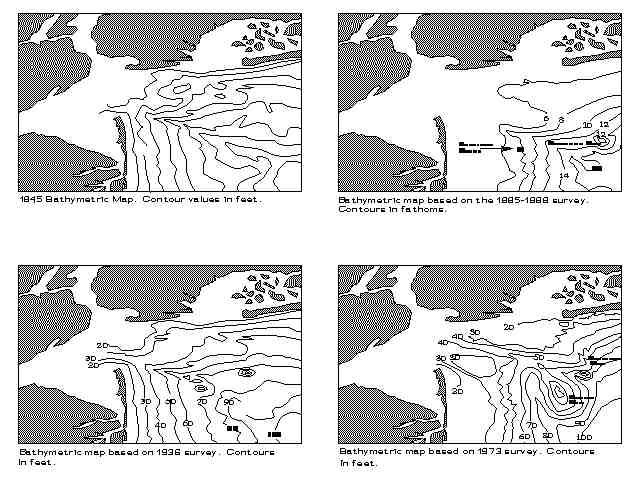

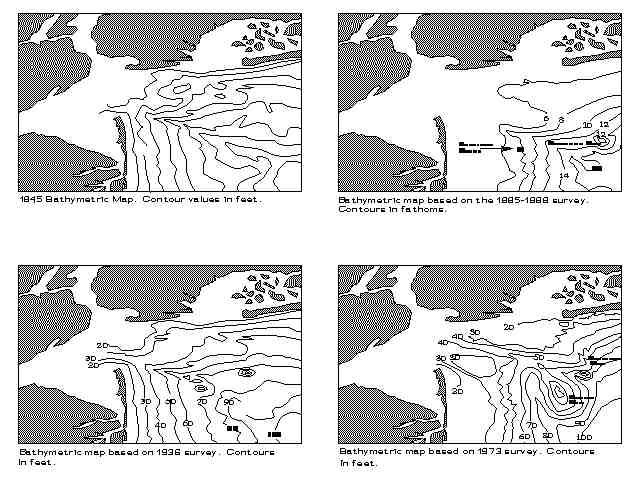

Few New York Bighters are aware of the incredible volume of debris contributed in the past to offshore dumpsites approved by U.S. Army Corp of Engineers. These official dumpsites have been in use since late in the 19th century and have been the repository of everything from household rubbish, cellar ash, and construction material to dredged sediments from shipping channels and building excavations rubble. Two undersea hills have risen on the sea bottom several miles offshore form both Sandy Hook and Breezy Point beaches (illustrated in the figure below). These hills have grown and eroded as materials have been intermittently dumped. The abundance of cinders on area beaches are evidence of this redistribution of sediments from offshore dumpsites. These materials will ultimately be reworked by coastal processes throughout the continental shelf and beyond in future regressions and transgressions of the sea.

Chemical and physical characteristics of anthropogenic materials (solubility, bioreactivity, density, hardness, size, and shape) help determine both how long materials are capable of persisting in the natural environment and where materials selectively accumulate. This is compounded by the quantity and rate that materials are generated, and by the method and location where materials are discarded.

Plastic is clearly the most problematic material in the environment because of its abundance, durability, and low density. It is a major hazard to marine life. Because of its low density it selectively accumulates on upper shore faces. Although an unsightly nuisance it generally degrades relatively rapidly (relative to other compounds) when exposed to sunlight or microbiotic activity. Plastic is problematic because it enters the ocean environment by many avenues, it is volummetrically abundant, and it currently escapes most practical recycling methods. Plastic on beaches comes from boaters, beach-goers, fishermen, street litter, and illegal dumping. Fortunately, the plastic debris problem is not as bad as it was in the 1960s to 1980s, thanks to a multitude of laws regulating ocean dumping, recycling, and landfill disposal.

Materials illustrated below represent common, problematic, and

unusual

anthropogenic materials collected on area beaches. Not all

anthropogenic materials

are "leaverites." During the collection of materials for this

report the writers found

money, gold jewelry, and both colonial and Indian artifacts.

However, a note of

caution before running off to the beach to collect... The amount

of money found in

relation to the hours spent collecting has only netted about

$.04/hour!

Indian arrowhead and pottery. Native American communities

probably existed in

lowland areas along the coast in areas now submerged during the

post-Ice Age

transgression. Stone and ceramic artifacts rarely survive

wave-grinding energy

and, therefore, are a scarce occurrence. Revisions to the

archeological record of the "New World" are constantly pushing

back the date of early human migrations into North America. An

article in the NY Times (Feb. 11, 1997, p. A1) describes

validation of archological sites at the southern tip of South

America as being over 12,000 year old. No doubt the NY Bight

shorelines (now submerged) were host to early, intermediate, and

late migrations of the ancestors of modern Native Americans.

Habitats along bays, beaches, and barrier islands they utilized

for food sources and settlements no longer exist.

Broken ceramic pottery, crockery, cookware were commonly

discarded from

ships and dumped by local shore residents since colonial times.

Prior to

enforcement of the ban on ocean dumping these materials were part

of the general

New York City garbage discarded at sea. Their abundance,

hardness and durability

ensure their long-term archeological significance into the

distant future.

Only bone that displays "butcher marks" (i.e. saw marks) can

truly be considered

anthropogenic in origin. However, bone of cow, pig, and chicken

are quite

abundant on

area beaches; probably the accumulation of years of weekend beach

barbecues

and ocean dumping.

Smelting of iron, slag from burning coal on ships and by local

residents are sources

of glass-like cinders that are abundant on area beaches. Cellar

ash was a major

constituent of materials dumped offshore.

Incorrectly discarded pavement material and coastal erosion is a

source of asphalt

on area beaches. Fragments of asphalt and slate shingles also

wash up on the

coast.

Wave-rounded brick material is fairly light and can be

transported long distances by

marine currents. Brick fragments make up substantial portions of

debris

on some area beaches where discarded building material has been

used as

fill.

Concrete generally cannot withstand long-term exposure to salt

water, compared

to other anthropogenic materials. However, because concrete is

both

fairly light and abundant it is common on local coastlines.

Freshly broken glass is a hazard on all area beaches.

Fortunately wave energy

quickly degrades sharp edges making smaller glass fragments which

are less

harmful, and are even pretty to look at. Glass is an extremely

stable compound

and will

likely survive in the environment for many millions of years.

Iron and aluminum cannot withstand long-term exposure to sea

water. Iron rusts,

commonly forming clotted chunks with attached shell debris.

Aluminum oxidizes

to

become gibbsite (clay). Other metals are scarce by comparison.

Silver, copper,

tin, zinc, lead, and most other metals eventually dissolve in

seawater.

Only gold and platinum can withstand long-term exposure in the

surface

environment.

Plastics are the universal "stratigraphic marker" material of the

20th Century. Most

plastic eventually degrades, but by shear volume and its ability

to float to

remote regions of the world guarantee its presence in the

long-term geologic

record.

Coal is extremely abundant on area beaches. It is impossible to

tell whether coal on beaches are anthropogenic waste or a

"natural" occurrence. "Sea coal" was noted in abundance on

beaches of Long Island long before coal was mined in the

Appalachian region. It's low density and durable character

allowed vast quantities of coal to survive long-term transport

processes by rivers from the Appalachian coal fields to the

Atlantic coast. Most is bituminous ("soft" Appalachian coal).

Today the coal on area beaches is a mix of natural "sea coal" and

coal that was probably spilled from ships or were mixed with

discarded cellar ash during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Anthracite deposits of eastern Pennsylvania were generally

depleted before the turn of the century. Fragments of

anthracite are common in glacial sediments in New Jersey and is

common in Cretaceous to Recent alluvial sediment throughout the

region. Some coal-like materials on area beaches represent

coastal swamp accumulations of peat and

estuary tidal flat deposits. Examples are illustrated in the

fossil section of this report.

Tar balls, waxes, grease lubricants, and industrial resins are

also common on area

beaches. These materials are potentially toxic and pose a

significant danger to

both wildlife and humans, particularly to children playing on the

beach.

Unfortunately, tarballs, like plastic debris, are universally

found throughout the world's

oceans.

Return to the

New York

Bight Home Page

Return to the

New York

Bight Home Page

Phil Stoffer and Paula

Messina

CUNY, Earth & Environmental Science, Ph.D. Program

Hunter College, Department of Geography

Brooklyn College, Department of Geology

In cooperation with

Gateway National Recreational Area

U.S. National Park Service

Copyright September, 1996

(All rights reserved; use as an educational resource

encouraged.)>